New Paintings

Gail Spaien: Painting as Navigation

by Suzette McAvoy

"Even an intensely inward experience of an artwork carries over to the experience of ordinary things," writes art critic and poet Carter Ratcliff in his essay, Why I Write About Art, "and that is because a limber sensibility, a sensibility energized and refined by interacting with a work of art, is also good at finding meaning in the flow of daily events. Our responses to artworks are warm-ups for responses to life."

Ratcliff's words came to mind after I visited Gail Spaien's studio, where several recently completed paintings were on the walls, and others were underway. We talked of "active looking," the gestalt of sensation, and paintings as "a site of exchange" between the painter and the viewer. "I like the directness of painting," she says. "I like to see an image materialize."

In the mid-1980s, while earning her M.F.A. at the San Francisco Art Institute, Spaien lived on the Mudlark, a small houseboat moored in Galilee Harbor in Sausalito. Living on the water in this unconventional community—where she learned to sail and "what it means to lead a creative life"— was a seminal experience, charting the course for her art and life. "The inside/outside nature of my work and also the notion of the floating cottage was inspired by my years living, working, and sailing on the water there," she says.

For the past twenty-five years, Spaien and her family, who live in South Portland, Maine, have spent several weeks each summer at the Hadden Cottage on Cliff Island in Casco Bay. The cottage architecture and island environment, as well as memories of her time on the water in Sausalito and summers spent as a child at Beach Park in Clinton, Connecticut, are deep sources of inspiration for her, providing the subject and sensibility for many of her paintings.

Mudlark Morning (2024) is a composite view, marrying the California houseboat, its interior open to the adjacent dock and a serpentine coil of mooring line, with the sparkling mosaic waters of Casco Bay, the stone tower and radiating light of Ram Island Ledge Light in the distance. A fresh breeze animates the sheer white curtain with its pattern of delicate leaves. At the table, topped with a woven runner and a clear glass vase of flowers, a cane-seated wooden chair sits invitingly at an angle, awaiting occupancy. To the right, a pair of ornamental yellow slippers, a nod to one of Spaien's favorite painters, the self-taught Morris Hirshfield (1872-1946), whose E-Z Walk Manufacturing Company produced a line of luxurious house shoes. The two artists, separated by time, gender, and background, share a mutual love for pattern and decoration, shifts in scale, and maximal opticality.

"A painting on a wall should be like a bouquet of flowers in an interior. These flowers are an expression, tender or passionate," said Matisse, the grand champion of the decorative in painting. For Matisse, decoration was not secondary but "an essential element." In Notes of a Painter (1908), he writes, "Composition is the art of arranging in a decorative manner the diverse elements at the painter's command to express his feelings."

In Spaien's Mudlark Morning, the composition and arrangement of elements recall Richard Diebenkorn's stunning tribute to Matisse, Recollections of a Visit to Leningrad (1965), painted shortly after he visited the Soviet Union and saw many of the French artist's masterpieces in person for the first time. Diebenkorn's painting, an abstracted window view with a floral arabesque "curtain" patterned after Matisse's Red Room, marked a turning point for him in its conflation of depth and perspective and strong geometric organization of space, anticipating the highly abstract Ocean Park series. Similarly, in Mudlark Morning, Spaien bisects the canvas with a broad vertical line, emphasizing the geometric underpinnings of the composition and melding interior and exterior space. "I'm a formalist at heart," she says, "I'm interested in the structure of paintings, I literally think of how things are built."

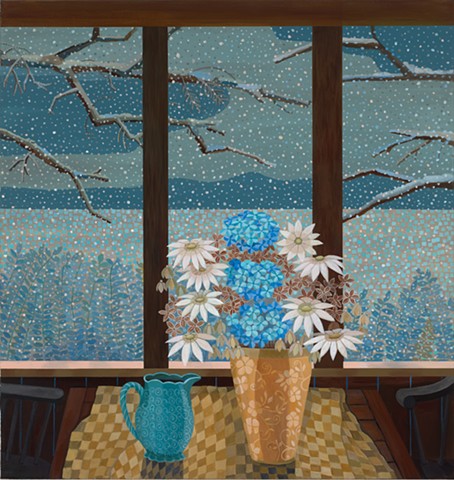

As an undergraduate at the University of Southern Maine, Spaien studied with the Latvian-émigré artist Juris Ubans, who told her, "The grid is a meditation," a sentiment she embraced and has long engaged within her work, providing symmetry and balance, and implied infinity. In a notable recent example, Ram Island Ledge, the interior of the Cliff Island cottage is centered on a large, gridded window, its vertical and horizontal lines reiterated throughout the composition, a dazzlingly harmonic orchestration of rectilinear shapes, with grace notes of curved forms in the braided rug, stout-handled pitcher, vase of flowers, and a sinuous line in the pale tan sky.

"In the stillness of this humble retreat from all the excitement of an agitated world, these everyday objects led their own, still life," writes John Reward in Visit with Morandi, an account of his visit to the Italian master's studio in 1967. Spaien's paintings of the cottage on Cliff Island, with its warm, wood-paneled walls and homey, simple furnishings, offer a comparable respite from society's ills. There is affection and reserve in these pattern-rich compositions, an invitation to share in the delight of daily life and a quiet formality to the ordered placement of things. I'm reminded of the words of author Seth Godin, "Here I made this. These four words carry generosity, intent, risk, and intimacy with them."

Since her days on the Mudlark, Spaien has had opportunities to sail offshore, out of sight of land, where "the edge between the sky and water is a space that is both anchored and groundless." Embedded in these recent paintings, pitched between land and sea, inside and outside, the domestic and the infinite, are sensations of time and tides, light, weather, and atmosphere. The horizon line is a determinant and destination, present and future, now and forever. Painting as navigation, as wayfinding, of knowing where we are.

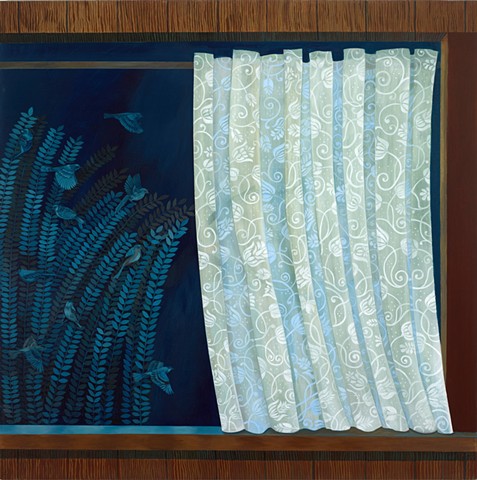

In Night Curtain, a minimalist arrangement of a darkened horizontal window half covered by a vertical white lace curtain, the push-pull of pictorial space, and Spaien's engagement with the yin-yang of abstraction and representation are especially evident. Seen through the window, the fronds of tall ferns populated with small birds and the gathered flower-patterned curtain bend toward one another, a duet of dark and light, the natural and the manufactured. The composition extends past the left edge and is framed three-quarters around by the faux-wood paneling of the wall. Cropping motifs and adopting the Abstract Expressionists' uncentered, allover compositional strategy, Spaien activates and gives equal weight to the entirety of the canvas. She is generous to the viewer, creating a perceptual experience that invites the eye to linger. Slowness, care, and solitude are conveyed through repetitive mark-making, a cycle she likens to "the experience of domestic time."

In these still, silent paintings, we hear the soft sound of the artist's brush, the tick of the clock, the rustle of leaves and birdsong, the lap of water against the shore, the incessant buzz of the world held at bay for as long as we are willing to look.

— Suzette McAvoy is an independent curator, arts writer, and museum consultant with more than thirty-five years experience in the field of fine art and museums. A leading authority on the art and artists of Maine, she has curated more than sixty exhibitions throughout her career, including nationally traveling exhibitions of the work of Louise Nevelson, Kenneth Noland, Lois Dodd, Karl Schrag, Alan Magee, and Alex Katz.

Photograpy: Luc Demers