"Before the taking of a toast and tea"

Nancy Margolis Gallery

November 2022

* The title for this show, Before the taking of a toast and tea, is a line from a T.S. Eliot poem From The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, 1910-1911. The line comes from a stanza that is particularly relevant in regards to sensations of time and space/ contemplation and anticipation I am trying to make visible in these paintings.

“There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

There will be time to murder and create,

And time for all the works and days of hands

That lift and drop a question on your plate;

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea.”

— T. S. Eliot

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Puzzle Pieces and the Sea’s Waves

Michelle Grabner

Sept 2022

Wing to wing and crest to crest, birds of every sort seize branches, air, and ground in a small and enchanting oil on copper painting by Flemish painter Jan Brueghel the Younger. Titled Allegory of the Air (1608) this brilliantly rich landscape lives in a salon among major and minor Renaissance and Baroque paintings, some of which include examples by Parmigiano, Bellini, Caravaggio, Durer, and Pieter Brueghel (Brueghel the Younger’s grandfather) at the Doria Pamphilj Gallery in Rome. The landscape’s organizational structure interlocks dramatic atmospheric energies with a stabilizing collection of numerous bird species that populate the foreground. The figure of Uranisa and a handful of chunky cherubs command the space in-between the earthbound aviary and the turbulent heavens.

Spending a remarkable amount of time with this painting over the past summer, I was taken by how the pleasures of this allegorical jewel aligned with my elated engagements with Gail Spaien’s recent paintings and their harmonious designs, window perspectives, and luminous abutting patterns. Besides the inclusion of birds, there is little if any visual vocabulary that unites Spaien’s paintings to this little Baroque treasure. Spaien’s system of flat interlocking color blocks, crisscrossing lines, and patterned fields are exuberantly choreographed with gradating values and warm hues to build remarkable albeit profoundly accessible pictorial spaces. Spaien employs a method and style that has more in common with Proto-Renaissance painting or of Henri Rousseau’s self-taught style than the soft gradual transitions of Baroque painting.

Style and technique aside, the splendid likenesses that Spaien shares with Allegory of the Air has to do with an orderly world and an embrace of rootedness. The specificity of the birds that inhabit Brueghel the Younger’s painting are so accurate and numerous that they would fill much of a European birder’s life list. A taxonomy this specific suggests that the artist was equally drawn to the beauty of the natural world as he was to the fantastical qualities of the allegorical. It is at this intersection where Spaien and the baroque painting unite. Celebrating the aesthetic and intellectual conditions of observation and the beauty of interconnectedness.

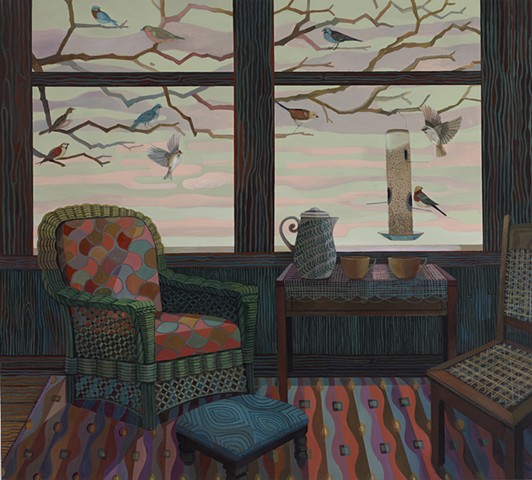

Spaien’s Observed Landscape #1, like Allegory of the Air also gathers together a range of bird species. They congregate in proximity to a tube-style bird feeder that hangs in a lattice of bare branches. The sparrows and buntings taking up residence filling the frame of the sash windows; an outdoor theater to an empty cottage sitting room where a wicker armchair with an upholstered footrest and a wooden caned high-back chair flank a table set with a coffee pot and two cups. The birds represent a vibrant sociability — enacting song, flight, and feasting — unpredictable spiritedness not familiar to the tidy and synchronized interior composed of carefully arranged patterns and early morning light. The space here, inside and protected from the natural elements of the outside world is staged for resting bodies in observation and contemplation.

A different set of sash windows gives way to a night sky dotted with stars in Observed Landscape #2. The seascape is depicted in an even accumulation of bright cerulean squares as faint Marsden Hartley-like clouds streak the darkness. Framed within the celestial field is an ascension of song birds whose colored feathers are illuminated by the brass banker’s lamp on the other side of the glass. Here the wood-trimmed interior hosts an attentive blue-eyed dog, a vase of symmetrically arranged flowers, and a throw pillow with a modern design. Spaien crafts a world within, interiors deliberately arranged with patterned objects and ornamented surfaces. She also paints a world beyond. It is a juxtaposition that underscores similarities, a stitching together of the bountiful in nature and domestic life. Spaien’s paintings manifest gratefulness with a sentiment akin to Jan Brueghel the Younger’s remarkably accurate depiction of the creatures of air.

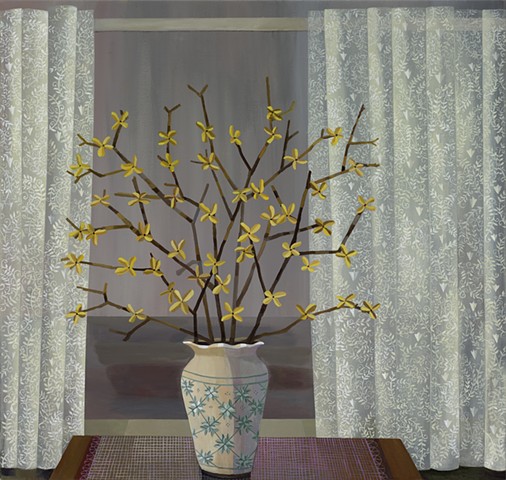

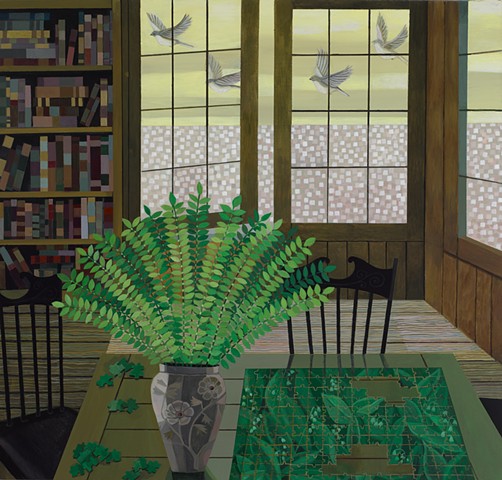

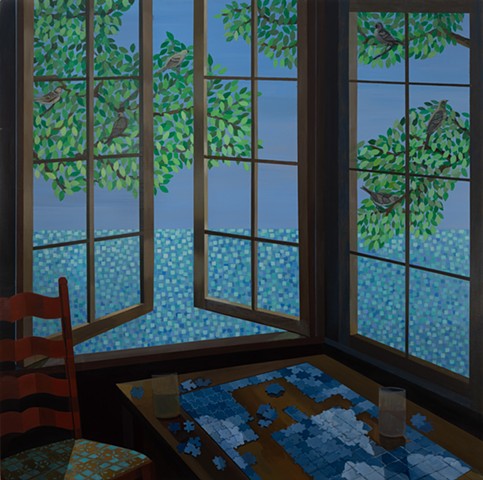

Spaien’s compositions are orderly worlds, peaceable kingdoms where beauty is compounded and the domestic is in accord with the natural just world beyond the panes of glass. Observed Landscape #7 opens the window between a welcoming room where a jigsaw puzzle is under construction and the leaf-laden branches where birds take roost in the landscape. The same with Observed Landscape #4, an interior room with a teeming library that opens up to a yellow veined sky with birds on the wing. The vertical stone fireplace in Observed landscape #3 is frontal and commanding when compared to the nook compositions with open windows. Here the interior cottage environment gathers a variety of chairs and domestic textiles in anticipation of company and the caretakers never pictured. Its night landscape recedes, a backdrop behind the well-mannered flames that celebrate the rootedness of hearth and home.

And it is rootedness, the foundations to place, to identity, and to time, that Spaien seeks to convey in her observed and imaginary compositions. Every element in her paintings has a place, a locked and secure location that is in harmony with every other element. It’s not just the bird's relationship to the sky or the chairs' relationship to its decorative cushions but the floorboards' kinship to the trees, the puzzle pieces' connection to the sea’s waves, and a curtain’s fellowship to wispy clouds. Literary critic Christy Wampole writes that “in the Western imagination, that transcendence is predicted on rootedness.” This is unambiguously evident in the Spaien’s effluent vernaculars but her imperturbable compositions are also tied to recognizable Eastern customs including Buddhist sand painting and the Japanese practice of bonsai. And like Brueghel the Younger’s Allegory of the Air, with its disciplinary arrangement of realistically depicted fowl that endow the allegory with rootedness, Spaien’s arrangements root our daily life with interlocking and strength-giving connectedness.

Michelle Grabner is an artist, curator, and critic based in Wisconsin. She is the Crown Family Professor of Art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Listen to the gallery talk here

Photograpy: Luc Demers